How Numworks killed third-party development - a technical approach

June 29, 2021Numworks is a French calculator manufacturer. When it was created in 2017, its main goals were intuitivity, ease of use, and openness. While Epsilon, their firmware, was never really open source, Numworks has been giving absolute freedom to the user to modify the software/firmware on the device, and now they’re taking away that user freedom, while also making the license less permissive.

We will first talk about the context in which this article is released and the closing down of the Numworks platform, then we will talk about the technical implementations of the restrictions put on the user.

Numworks: From an open platform to a closed system

Once open a time, when Numworks was an open platform

At the beginning, Epsilon, the Numworks’ firmware, was licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND, which caused problems for the potential contributors of Epsilon, because it was technically illegal to fork Epsilon, make changes, and create a pull-request on Numworks’ repository. In 2018, everything changed, as they decided to change the license to CC-BY-NC-SA, thus giving the user the right to edit the firmware. This didn’t mean that the firmware was Open Source. This is a common mistake people make, Epsilon was never open source in the way the Open Source Initiative or the FSF describes it.

The real strength of the Numworks calculator was that you could install whatever you wanted on it. This led to the creation of many community-driven projects, like Omega or Delta.

But then, issues arose

First, Numworks’ way of handling international development was to only have a single model for the whole world. This would lead to issues about countries forbidding symbolic calculation at exams. Epsilon’s calculation engine, Poincaré, was technically capable of doing symbolic calculations, but this capability was disabled in Epsilon. It was re-enabled in Omega, which could be installed on any calculator. Whilst this doesn’t cause issues for countries like France or Germany, this is problematic for countries like the Nederland or Portugal, which forbids Symbolic Calculations at exams. The development of KhiCAS for the N0110 didn’t help either, as it was way more powerful than Poincaré.

Secondly, the openness of the calculator lead to irresponsible people cheating on exams. Some people, like Maurits van Altvorst went even further and explained how to cheat, and went as far as contacting government entities to tell them about the “issue”.

Epsilon 16: New security measures to restrain the user’s freedom

With Epsilon 16, Numworks decided to completely close their platform down. This has a lot of consequences for the community, because the new measures forbids the permanent installation of unofficial firmware. You can still run them, but if the calculator resets, it will start a fresh copy of Epsilon, meaning you have to reinstall the unofficial firmware if the calculator crashes, goes in exam mode or the battery dies.

What is the point to continue maintaining Omega if people can’t use it properly? They will indeed kill community development with these measures.

Taking a look at the measures, from a technical point of view

This is the fun part. When the Beta of Epsilon 16 was released, I immediately started disassembling and decompiling it using Ghidra, and found some interesting stuff.

Setting up Ghidra

If you want to give it a try too, you can set Ghidra up and try yourself. I’ve created some scripts to download the Beta and extract the internal and external binaries. I also wrote a guide, in French, detailing how to set Ghidra up.

Internal flash: the bootloader

The internal flash is dedicated to a custom-made bootloader. This bootloader seems to be based on the code of Epsilon, integrating Ion and some parts of Kandinsky. It performs initialization of most of the hardware (MPU, GPIOs, Screen, Keyboard, Timers, External flash) and reads the content of the external, looking for a valid OS.

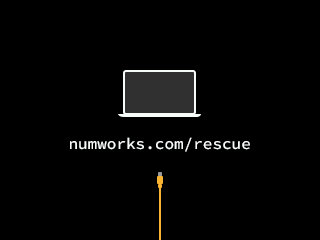

The bootloader first check for an OS in the lower half of the flash. To determine if an OS is valid, the bootloader performs an ED25519 signature check. The implementation seems robust. If the OS is good, it boots it, if not, it tries to validate a second OS, located in the upper half of the external. If no valid OS is found, the bootloader starts a USB stack, the same used in current Epsilon, with a DFU interface available, and shows this screen:

In the current beta, the bootloader is easily patchable. You can either create new keys and inject them in the bootloader (thus having the ability to self-sign an OS) or completely bypass the signature check (Both patches are available in the scripts in the repo I linked). The latter should be avoided, as the OS also seems to check for signature, showing a message if it can’t authenticate itself. The message isn’t shown when changing the keys. In the future (aka. the final release of E16), it won’t be that simple to patch the bootloader, as it will be non-rewritable. This is a thing that must be done once with the final release, and if you do it, don’t lose your private key, or your calculator will end up bricked. This isn’t viable as a long-term attack, as the new models preloaded with E16 won’t be patchable, since the bootloader will be non-rewritable.

It is worth noting that the bootloader gives full privileges to the OS when booting it, it should therefore be easy to boot Omega on that thing once the structure of the OS are understood (I’m working on it).

External flash: The Kernel and the userland

When the bootloader has validated the OS, it boots it. As said before, the external flash is split in half, the lower half for the main OS and the top half for the “rescue” OS (aka. the one launched when you reset if you “installed” a custom firmware). Each half is split in three parts :

- The Kernel, currently at offset 0x10000. It’s the thing that is booted by the bootloader.

- The userland, currently at offset 0x50000. It’s launched by the kernel after it has fully initialized.

- The signature, currently at offset 0x1429dc (variable offset). 64 bytes, the ED25519 of the OS.

The kernel is responsible for the initialization of the rest of the hardware (modification of the MPU memory layout, …). It also handles Supervisor Calls and launches the userland. The userland is your typical Epsilon, with all the apps, poincaré, micropython, …

The kernel can also show warning messages at boot, if the OS has external apps installed, or if a custom firmware is used.

Conclusion

This is a sad day for the Numworks community. These are some really hard and violent restriction on what the user can do with the hardware he owns, and a step in the wrong direction. Numworks has taken a 180° turn in its philosophy, for the worse.

The technical aspect behind this is fascinating to me, as it is the first time I really dig into an embedded device’s firmware using Ghidra. No exploits apart from patching have been found yet. I sincerely hope the community will manage to free itself from these drastic restrictions by developing an exploit allowing to bypass the signature check of the bootloader.

I’ll post a new article when Epsilon 16 is released, with an update on my findings, and updated scripts.